For the love of the game or the money?

Name, Image and Likeness, also known as NIL, is a very prominent topic in college athletics today. There's been debate over whether college athletes should be paid, how they should be paid, and the pros and cons to allowing students to monetize their name.

Navigating a new period of NIL

NIL has taken over the news of college sports for over 10 years now. It’s a constantly changing landscape, with controversy and heavily opinionated spectators all over. It's also a complicated layer with no easy answers.

Name, Image and Likeness, or NIL, gives student athletes the legal ability to monetize their name and enter contracts with third parties. The current setup, however, is flawed.

“It’s restricting students who play sports from the economic rights of all students,” ASU professor and sports historian Victoria Jackson said. “If you have athletic directors and NCAA officials saying ‘No, no, student athletes are like all other students, we can’t pay them,’ you’re not treating them like all other students when you restrict them from their economic rights.”

Jackson believes this shows the hypocrisy of the NCAA, who has battled against NIL. Its argument is that college athletics are amateur sports. The problem arises when not paying these athletes restricts their value.

It’s also arguably a violation of antitrust laws.

“Placing an artificial cap on a category of people’s income is a violation of antitrust law,” Jackson said. “You’re acting in a monopolistic way when you’re setting a limit on what the market can do for someone.”

Antitrust laws arm student athletes with a way to fight against the NCAA, since court judges won’t choose amateurism over the law. If regulations are putting a cap on an athlete’s worth, it’s violating the law.

There are other issues with NIL regarding inequity.

“Are you paying your football players more than all the other sports? Are you paying men’s basketball more than women’s basketball? That starts getting into Title IX issues,” Dr. Cody Orr said. Orr attended Baylor University before getting his Ph.D in economics, and he wrote a blog post on his concerns regarding NIL.

Title IX refers to the regulation that all students need to be fairly compensated, or at least exposed to the same opportunities. But is NIL unfair from the start?

This video offers a non student athlete's perspective to the NIL controversy.

A Division I football athlete isn’t going to rake in the same kind of NIL deals as a Division III swimmer.

“There’s nothing fair about NIL,” Jackson said. “Just because something isn’t fair, doesn’t mean you shouldn’t allow people to tap into it at all.”

Spectators have proposed giving student athletes a salary to replace NIL and still compensate them. Jackson proposes setting media rights evaluations to try to keep salaries fair.

“The Pac-12 Conference had annual revenue from their media rights deals, and it’s distributed to each school. And what percentage of that media rights is football? Okay, that percentage goes to football, and maybe it’s 50/50 media rights revenue sharing,” Jackson reasoned.

But salaries carry their own burden.

“You don’t want to end up in a situation where you put a burden on every university to compensate every athlete the exact same amount, and then make it so that the university has to close down certain sports in order to have that perfectly equitable amount,” Orr said.

The Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication has started a project known as the NIL Research Initiative, which compiles data relating to NIL from universities nationwide. The aim is to find trends and predict where NIL is heading.

“NIL is really cutting across all aspects of collegiate athletics, in that it’s also influencing recruiting and influencing transfers, where athletes are going from one program to another, perhaps seeking better opportunities through name, image and likeness,” Dean Battinto Batts, a member of this initiative, said.

The initiative has struggled with getting enough data to provide a holistic view of NIL trends. This is because athletes aren’t obligated to release information on their brand deals.

“We don’t have enough data to give a firm analysis right now of what ASU is doing. But, if you can look at some of the things that have been in the news, it’s obvious that ASU is intending to be as much of a player in NIL as other schools,” Batts said. “Independent of the NIL project, ASU intends to offer as many opportunities as it can for athletes.”

The setup of NIL is bound to continue changing. Is there a viable solution to improve it?

“At some point, the policymakers have to decide who is the most important constituent. Is it the universities? Is it the fanbases, or is it the student athletes?” Orr said. “And how do we weigh those different groups? Until we know who we value, you can’t design an optimal policy.”

“Why we got into the NIL project is to provide more information about what NIL is, what the trends are, and how it’s impacting collegiate sports,” Batts said. “So if there was anything that I would hope to see more of is just more information sharing and understanding what's happening in the NIL realm, and what that can mean for the future of athletics.”

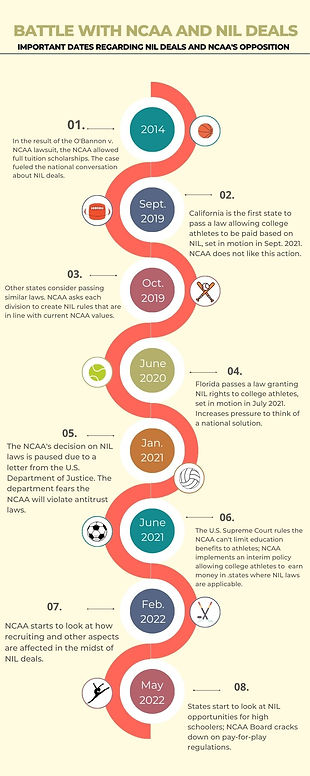

Take a peek at the infographic above to learn important dates regarding NIL. Click on the slideshow to read about the different places where the Sun Devils compete.

Taken at the Desert Financial Arena, this was a meet for both the gymnastics team and the wrestling team.

This shot was at a men's hockey game here at Mullett Arena.

This picture captures women's water polo at the Mona Plummer Aquatic Center here in Tempe.

Taken at the Desert Financial Arena, this was a meet for both the gymnastics team and the wrestling team.

ASU gymnasts making new strides with their names

Over a year ago, the NCAA set new regulations for college athletes to make money off NIL. The parameters of these regulations are still shaky, but nonetheless, student athletes at ASU are beginning to create a brand for themselves.

Junior Cassi Barbanente has been competing for the gymnastics team since her freshman year and is taking advantage of the changing landscape of NIL.

“My most current and most active NIL deal I have going is with a nutrition bar called Feel Good Nutrition,” Barbanente said. “They reached out to me in the fall, and so I went in, they gave me a discount, I tried their products, and I really liked them.”

Barbanente connected with the owner of the brand, who was a college athlete herself, and she soon became the first athlete sponsor for Feel Good from ASU. It’s a mutual deal: the gymnast gets discounted products in return for posting the brand on social media.

One concern regarding NIL deals is that the obligations take up the little free time college athletes have, but Barbanente doesn’t think it’s too much.

“Especially not for me because I’m one whose brain is wired that way. I’m pretty creative, and I enjoy TikTok, I enjoy Instagram, and those are things that I would do anyways,” she said.

Barbanente’s teammate, junior Jada Mangahas, has also scored NIL deals, her most prominent one being with Adidas.

“On this app called Post Game, which is an app where a lot of athletes will go on to get connected with brands, and you can opt in to different brand deals to get your name out there,” Mangahas said. “I just kind of put my name out there for the Adidas one because our school’s sponsored by Adidas, so we were eligible for it.”

The partnership is a similar idea to Barbanente’s in that Adidas sends Mangahas clothes, and she promotes certain sales on social media.

Because NIL is so recent, ASU is still trying to navigate how to help students, and their tactics have mixed reviews.

This short podcast episode goes into more detail about a gymnast's experience with brand deals.

“[ASU’s workshops] teach you how to market yourself, how to really stay true to yourself, and how to best utilize your brand in order to get NIL deals,” Barbanente said. “Obviously, they can’t go out and get them for you. You kind of got to do that yourself. But I definitely like the workshops that they hold.”

Mangahas had different thoughts.

“They kind of tell you, ‘Oh, these are the rules, this is what you’re allowed to do with brands, etc.,’ but I feel like they don’t really give you a path on how to do it,” Mangahas said. “I think you kind of have to learn from your own experience, or ask somebody who’s gotten experience themselves. I think ASU could do more with being more individualized.”

Despite this, there are benefits to NIL for these girls.

“I’m building a new community and growing kind of with them as I’m growing as an athlete here at ASU too,” Barbanente said. “And something I never predicted for myself because coming into college, it wasn’t like that.”